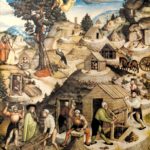

1. The medieval mining area

Emperors, kings, princes and mineworkers

In contemporary documents, you can learn much information about the techniques and organisation of the mining industry as well as about the mineworker’s life and work in the middle age. A document from 1028 is the oldest written reference to the mining industry in the southern Black Forest. With that document the emperor Conrad II granted rights to the bishop of Basel to extract silver in the mines of Breisgau. The mines situated in Münstertal, Sulzburger Tal and near to Badenweiler are mentioned, too, in that document.

The oldest written mining code is from 1208 and ruled the organisation and work in the mining industry. However, it also provides information about the exploration, extraction and treatment of resources.

Economically free mineworkers operated the extraction and exploration of silver on behalf of the landlord or prince to whom was conferred that right by the emperor or king. The landlord, prince or reeve was responsible for the protection and defence of the mineworkers and mining area.

Mining area in the Ehrenstetter Grund

In the Ehrenstetter Grund, two parallel running lead-silver veins cross the valley of the “Ahbach”. In this area, the medieval mining searching for these veins has left clear and lasting marks on the surface. The mountain is traversed by galleries and shafts, just like a Swiss cheese. Nowadays, these still open cavities are called “Lingelelöcher”.

So far there is no medieval heritage from this mining area. In 1991 the Institute for Pre- and Early History of the University of Freiburg carried out a prospection and documentation of the still visible traces in the mining area. The ceramic fragments which were found in the shafts and slag heaps, were dated to the 13th and 14th century.

However, till now there have been no archaeological excavations. Therefore, we do not really know where the ores had been treated and smelt. The mineworkers lived in the vicinity of the mining area; possibly at the entrance of the valley near the “Streicherkapelle” (chapel) which has already been mentioned in a document of 1554. Near the “Lehenhof” stone box graves, dated 800 AC, were found. They provide information about the probable existence of an old a possible settlement.

How do you extract silver from the stone?

In former days, the mineworkers searched for silver ores and the presence of galena which consisted mainly of lead and only between 0.1 and 1 percent of silver (i.e. 1000 kg galena = 1 to 10 kg silver). They found the silver veins by means of screes in streams and by means of blowouts at the place where the veins come to the surface.

At first, near the surface, the veins were exploited in opencast mines by entanglements. In later times the mineworkers built a system of horizontal galleries and vertical shafts enabling them to exploit the veins at greater depths. Galleries and shafts had led the mineworkers first through waste rock, till they arrived at the mining location, the vein.

The treatment and melting of the iron ores took place in close proximity to the mines. During the treatment, the extracted ores were chopped, separated from mineral rocks such as quartz and gneiss and ground fine. Then they produced an ore concentrate consisting of silver and lead by washing out the vein material and by roasting (sulphur contents volatilize when they are heated). This ore concentrate was melt in the smeltery. The needed coal for this process was provided by charcoal makers in the vicinity of the mine sites. At temperatures above 1200 degrees, they obtained an argentiferous lead. In the refining furnace the silver was separated from the lead and delivered in form of silver bars to the mints in Breisach and Freiburg.